JOSE RIZAL AND PHILIPPINE NATIONALISM: Bayani and Kabayanihan

HERO vs. BAYANI

In mythology, a hero is someone who possesses great courage, strength, and is favored by the gods. The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines "hero"

as "a mythological or legendary figure often of divine descent endowed with great strength or ability; an illustrious warrior; a person admired for achievements

and noble qualities; one who shows great courage.”

The Filipino counterpart, bayani, has a similar meaning but with some contextual distinctions. Bayani is someone who fights with his ‘bayan’ or community. The

Vicassan's Dictionary (Santos, 1978) provides the following meanings for bayani:"... hero, patriot ("taong makabayan"), cooperative endeavor, mutual aid, a person

who volunteers or offers free service or labor to a cooperative endeavor, to prevail, to be victorious, to prevail ("mamayani"), leading man in play (often referred to

as the "bida"--from the Spanish for life, "vida"--who is contrasted with the villain or "kontrabida" from the Spanish "contra vida", against life)” as cited in Ocampo, 2016.

UP Diksiyonariyong Filipino (2001) gives three meanings for 'bayani': (1) a person of extraordinary courage or ability; (2) a person considered to possess extraordinary

talents or someone who did something noble ("dakila"); and (3) a leading man in a play (Ocampo, 2016).

The Vocabulario de la lengua Tagala by the Jesuits Juan de Noceda and Pedro de Sanlucar (1755 and1860) lists these meanings for bayani: "someone who is brave or valiant,

someone who works towards a common task or cooperative endeavor ("bayanihan") ( as cited in Ocampo, 2016).

History professor Ambeth Ocampo sees it significant that bayani comes a few words under bayan, which is also defined as: "the space between here and the sky." Bayan is

also a town, municipality, pueblo, or nation, and can refer to people and citizens (mamamayan) who live in those communities, or those who originate or come from the

same place (kababayan). Bayan (Ocampo, 2016) also refers to the day (araw) or a time of a day (malalim ang bayan) or even to the weather, good or bad (masamang bayan).

Ocampo, thus, concludes that "hero" and bayani do not have the same meaning. Bayani is a richer word than hero because it may be rooted in bayan as place or in doing

something great, not for oneself but for a greater good, for community or nation.

OFW:Modern Heroes

THE CHANGING FORMS AND DEFINITIONS OF BAYANI AND KABAYANIHAN

Anchored on the definitions given by old dictionaries, mga bayani may historically (and profoundly) refer to those who contributed to the

birth of a nation. In the early times, heroes are the warriors and generals who serve their cause with sword, distilling blood and tears;

they are those, for the Filipinos, who served their cause with a pen, demonstrating that the pen is as mighty as the sword to redeem a people from their political slavery.

However, the modern-day bayani may refer to someone who contributes to a nation in a global world.

In modern definitions, a Hero is: someone who has distinguished courage and ability, someone who do good deeds for the greater good of others,

and mostly works alone. One case in point is our Overseas Filipino Workers ( OFWs) — Filipinos who are working in foreign

countries who basically travel abroad in pursuit of better employment to provide for the needs of their respective families in the Philippines. The OFWs’ sacrifices play a vital role in the progress of the Philippines’ economic status — by remitting their savings back to the country, they help the government in pulling up the economy through the overall dollar reserve. The money that they send provides the much-needed hard currency, saving the country from defaulting debt obligations. Aside from this, they also help stabilize the Philippine Peso in relation to peso-dollar exchange, which in turn, contributes to the country’s Gross National Product (GNP) growth. Truly, when they work abroad, they are taking risks (pakikipagsapalaran) and in recognition of their sacrifices, they are named Bagong Bayani or “Modern-Day Heroes”, acknowledging their contributions every December as the Month of Overseas Filipino Workers.

Many Filipino bayani have fought and died for the Philippines, some of which are Jose Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, Apolinario

Mabini, and many more. They can be considered as traditional Bayani, someone who fought for the people of his community and

for their greater good, and died in exchange. But in our modern world, does our country need a bayani who will sacrifice his/her life for the country?

Without a doubt, the concept of bayani and kabayanihan have evolved through the years. To better understand this evolution,

let us compare the notion of OFWs as modern-day heroes to the early definitions of bayani. Its etymology is explained in an

online article entitled, “Ang Salitang Bayani sa Pilipinas” (n.d.)

salitang “bayani” ay isang Austronesian na salita na dinala ng ating mga katutubo sa ating bayan. Ang mga bayani ay ang mga

mandirigma kung saan sila ay nangunguna sa pagtatanggol ng pamayanan laban sa mga kinakaharap na mga kaaway at panganib. Ang ilan

sa mga diribatibo ng salitang bayani ay bajani, majani, bagabnim, bahani.

Sa kultura nating mga Pilipino, ang pagiging bayani ay nasusukat sa katapangan at sa bilang ng napapatay na kaaway. May iba’t-iba

itong antas. Ang mga antas na ito ay kinikilala bilang: 1) Maniklad, ang pinakamababang uri ng bayani na nakapatay ng isa o dalawang

kaaway, karaniwang siya ay nakasuot ng putong na pula at dilaw; 2) Hanagan naman kung tawagin ang nasa ikalawang antas, siya ay

sumasailalim sa ritwal na kung saan ay dapat siyang sapian ni Tagbusawa, ang diyos ng pakikidigma at kainin ang atay at puso ng

mga kaaway. Karaniwang nagsusuot ang mga ito ng pulang putong; 3) Kinaboan naman kung tawagin ang makakapatay ng dalawampu hanggang

dalawampu’t pito at karaniwang nakasuot ng pulang pantalaon; 4) Luto naman kung tawagin ang makakapatay ng limampu hanggang 100 na

kaaway at karaniwang nagsusuot ng pulang jacket; 5) Lunugum naman ang pinakapaborito ng diyos na si Tagbusaw dahil dito maipapakita niya

ang kanyang katapangan sa pakikipagdigma kung saan napatay niya ang kanyang kaaway sa sarili nitong tahanan. Itim ang karaniwang suot ng mga ito.

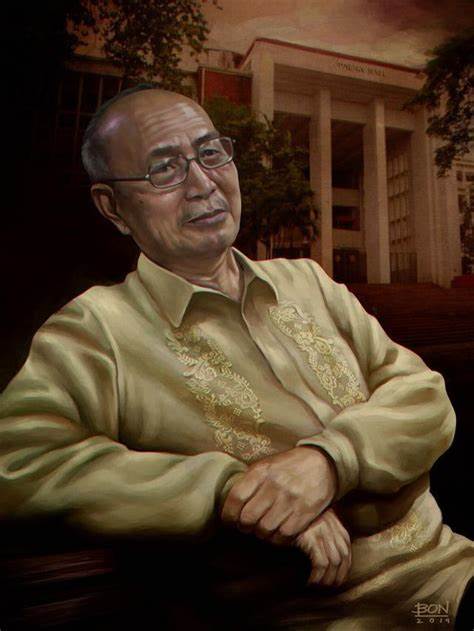

Dr. Zeus A. Salazar

Father of New Philippine Historiography and Pantayong Pananaw (For-Us-From-Us Perspective) Proponent, Dr. Zeus A. Salazar gives a different definition of the term bayani.

In fact, he believes that bayani is different from “heroes.” For him,

“ang mga bayani ay mga taong naglalakbay at bumabalik sa bayan… ang mga bayani ay lumalaban ng may kooperasyon

[samantalang] ang mga hero (western concept) ay lumalaban mag-isa… Ang bayani ay hindi kailangang mamatay upang

maging bayani... Kailangan niya lang gumawa ng magagandang impluwensya at mga gawain sa bayan upang

tawaging bayani (Ang Salitang Bayani sa Pilipinas, n.d.).

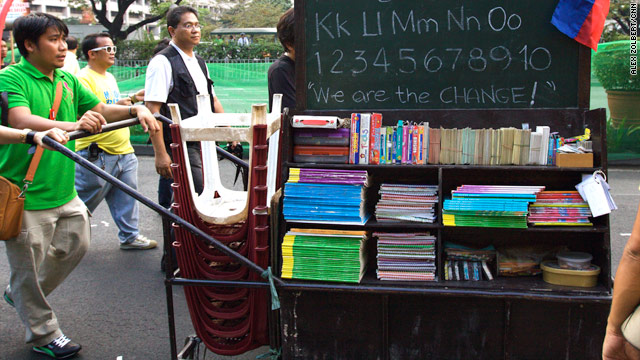

Efren Peñaflorida and his Pushcart Classroom

person has a hidden hero within, you just have to look inside you and search it in your heart, and be the hero to the next one in need.” – Efren Peñaflorida

WHY IS RIZAL OUR GREATEST HERO?

In an article entitled, “Who Made Rizal Our Foremost National Hero and Why?,” the author, Esteban A. de Ocampo,

denies the claim that Rizal is a made-to-order national hero manufactured by the Americans, mainly by Civil Governor

William Howard Taft. Instead, he defended Rizal as the country’s foremost hero. This was done, allegedly, in the following manner:

"And now, gentlemen, you must have a national hero". These were sup-posed to be the words addressed by Gov. Taft to Mssrs.

Pardo de Tavera, Legarda and Luzurriaga, Filipino members of the Philippine Commission, of which Taft was the chairman. It

was further reported that "in the subsequent discussion in which the rival merits of the revolutionary heroes (Marcelo H. del Pilar, Graciano Lopez Jaena, Gen. Antonio Luna, Emilio

Jacinto were considered, the final choice—now universally acclaimed wise one - was Rizal. And so history was made."

De Ocampo’s justification is founded on the definition of the term “hero,” which he took from the Webster’s New International Dictionary of the English Language,

that a hero is "a prominent or central personage taking admirable part in any remarkable action or event". Also, "a person of distinguished valor or enterprise

in danger". And finally, he is a man "honored after death by public worship, because of exceptional service to mankind".

Why is Rizal a hero, more correctly, our foremost national hero? It was said in the article that he is our greatest hero because he took an “admirable part” in

the Propaganda Campaign from 1882-1896. His Noli Me Tangere (Berlin, 1887) contributed tremendously to the formation of Filipino nationality and was said to be

far superior than those published by Pedro Paterno’s Ninay in Madrid in 1885; Marcelo H. del Pilar’s La Soberania Monacal in Barcelona in 1889, Graciano Lopez

Jaena’s Discursos y Articulos Varios, also in Barcelona in 1891; and Antonio Luna’s Impresiones in Madrid in 1893. This claim was evident in the comments that Rizal

received from Antonio Ma. Regidor and Professor. Ferdinand Blumentritt. Regidor, a Filipino exile of 1872 in London, said that "the book was superior" and that if

"don Quixote has made its author immortal because he exposed to the world the sufferings of Spain, your Noli Me Tangere will bring you equal glory…"